Material Impact

Total hip arthroplasty is a common surgical procedure undertaken to relieve pain and restore function. According to OECD Health at the Glance 2017, more than 172 hip procedures per 100,000 of population were performed in OECD countries. The hip procedure rates increased by 30% between 2007 and 2017 and they are expected to rise in future following the growing incidence of osteoarthritis due to sociodemographic changes. The increase of multi-morbidity cases contributes significantly to this trend.1

Healthcare systems are currently facing challenges in financing and provision of medical services and will do so even more in the future. In the face of these epidemiological and health economic developments, the choice and efficiency of the medical intervention are becoming essential in the long term. In total joint arthroplasty, the choice of the implant material increasingly plays a pivotal role.

Current Evidence

International registries show a growing trend in the use of ceramic implants in primary hip procedures. Ceramic components are perceived as a reasonable choice. Countries such as Italy, Germany, France and Korea adopted ceramic solutions very early on, however, in other countries like the USA or in the UK, only recent issues and concerns about fretting corrosion led surgeons to use ceramics instead of CoCr heads.2-9

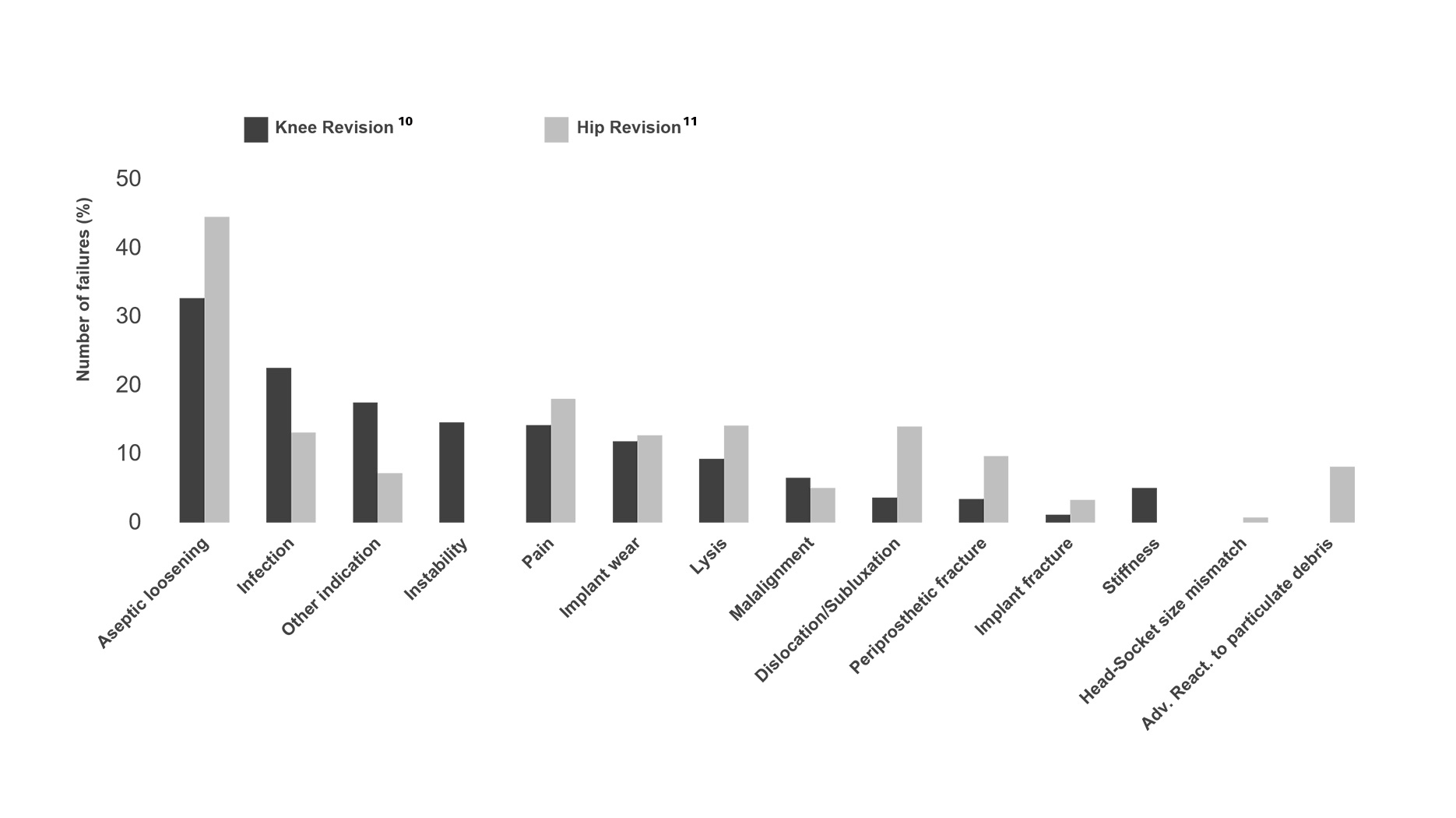

Even though modern biomedical research and constant development of orthopedic implants have improved the clinical outcomes over time, some challenges still need to be faced. Among the most common reasons for revision in TJA, are aseptic loosening, infection, dislocation, periprosthetic fracture and pain. Although these complications are mostly associated with uncertain etiology the bearing material plays an important role.

Patient’s Risk Factors

Several factors besides implant material determine the clinical outcome of a TJA surgery, including patient-specific factors, such as gender, age, living habits, and medical history. Before operating on a patient, surgeons will look at each case individually and make sure that the patient’s risk factors are taken into consideration when choosing the right treatment regime.

Influence of Smoking

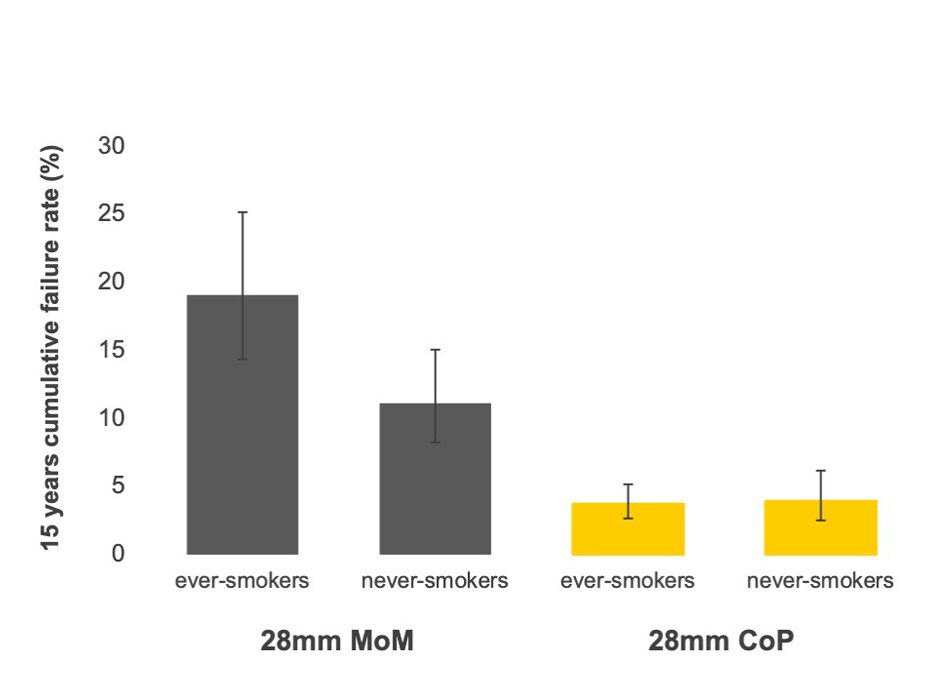

A recent observational prospective study (Geneva Arthroplasty Registry, Switzerland) investigated the relationship between patient smoking habits, bearing material and the risk of revision in THA. The study revealed that the use of metal bearings is associated with a high failure rate, especially in ever-smokers (compared to never-smokers). In contrast, the low failure rates with ceramic-on-polyethylene bearings were not associated with patient smoking habits (ever smoker vs. never-smoker).12

Take Away

A study suggests that ceramic bearings possibly do not compromise patients’ health status even if the patient is already at a risk (e.g. smoking habits).

Immune Response to Implant Material

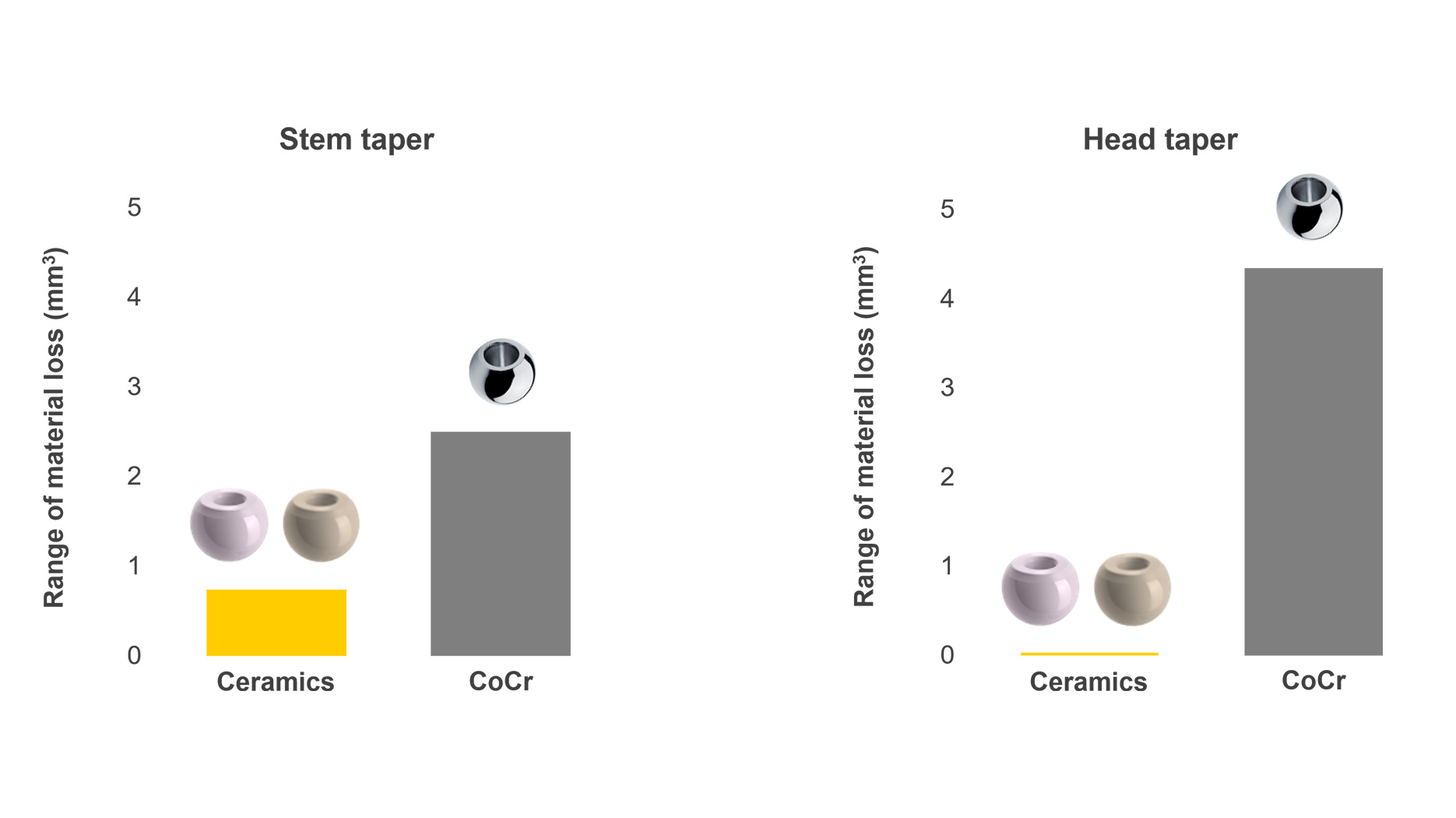

Adverse reactions to TJA-implants can be related to fretting and corrosion or wear and particulate debris (especially metal). These can trigger local or even systemic tissue inflammatory reactions. Bone, muscles and nerves surrounding the implant can be extensively damaged, ultimately leading to a revision surgery for adverse reaction to metal debris (ARMD).

ARMD includes local and systemic tissue reactions and can manifest itself in the form of osteolysis, necrosis, pseudotumor or fibrous capsules and can be associated with elevated blood/serum metal ion levels and metallosis. ARMD and trunnionosis are often accompanied by a high risk of serious complications and have also been associated with the development of hypersensitivity.

Although clear implant-related metal toxicities are rare, the clinical findings in patients with high metal ion levels and particle concentrations are devastating and have been shown to be associated with an enhanced risk for the development of periprosthetic infection, inflammation, local tissue toxicity, carcinogenicity, and genotoxicity.

Ceramic is safe in terms of metal ion release13 and pathogenic reactions to ceramic particles are unlikely14. Even if metallosis and hypersensitivity remain rare, ceramic heads may be especially indicated in cases where the use of CoCr heads might compromise the health of the patient, and in patients with comorbidities, such as impaired renal function or known metal hypersensitivity.

Corrosion Resistance

Mechanically Assisted Crevice Corrosion (MACC) in modular total hip arthroplasty was identified as a clinical concern in the 1980s-90s. Design trends like metal-on-metal and metal-on polyethylene bearings with large heads and modular necks have re-introduced implant corrosion at the junction taper as a clinical issue, this being the cause for 8.2% of all revisions11 and often with serious consequences.

This concern led many surgeons to rethink their treatment algorithm and eliminate the use of CoCr head by replacing them with ceramic heads. Ceramic heads have proven to be very effective at limiting corrosion thus mitigating the generation of toxic byproducts. A study by Kocagoz13 and a recent meta-analysis by Wight et al.15 show that the use of ceramic heads mitigates the problem of fretting corrosion and is therefore a reasonable option.

Infection Prevention

In-vitro studies have shown that bacteria adhere less to ceramic surfaces. Researchers at the University of Bristol investigated how this observation transfers into clinical outcomes. In their study published in the LANCET, Lenguerrand, Whitehouse, and co-authors investigated the risk factors, their correlation and impact on the risk for revision due to PJI. The factors investigated were patient-derived, such as age, gender, etc., health system-derived factors such as place of surgery, operating surgery volume, etc. and surgery-specific, such as osteoarthritis, fracture of femoral neck, etc. In this study, bearing type was also assessed and thus, the investigation of the impact of bearing material on PJI.16

In addition to patient-related factors such as elevated BMI, diabetes, male sex and others, metal bearings were identified as a risk factor for revision because of PJI.

Implant Stability

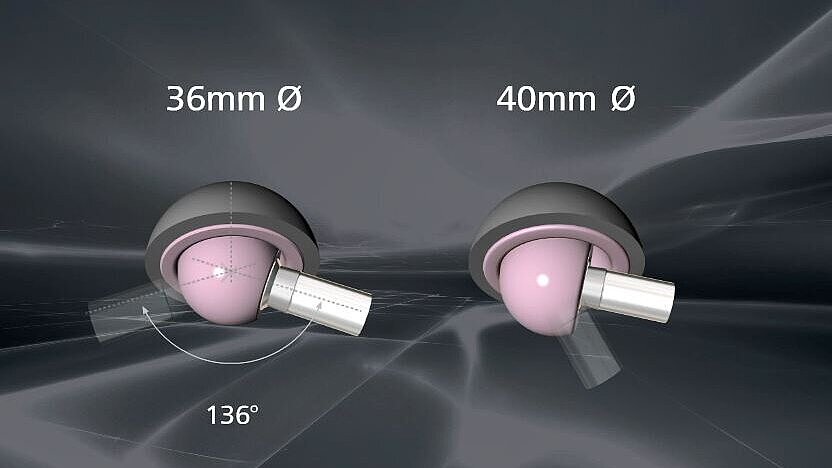

Dislocation is one of the major causes of revision after primary THA accounting for about 15% of all revisions in the UK National Joint Registry. It is an early complication, and patients who suffer from a first dislocation will likely experience one or more further dislocations. Dislocation patients seem to benefit from ceramic bearings. One of the reasons is that ceramic allows the possibility of increasing the head diameter, optimizing the range of motion without increasing wear17. Studies suggest that Ceramic-on-Ceramic bearings may be associated with less late dislocations than polyethylene bearing surfaces18.

Best Clinical Outcomes

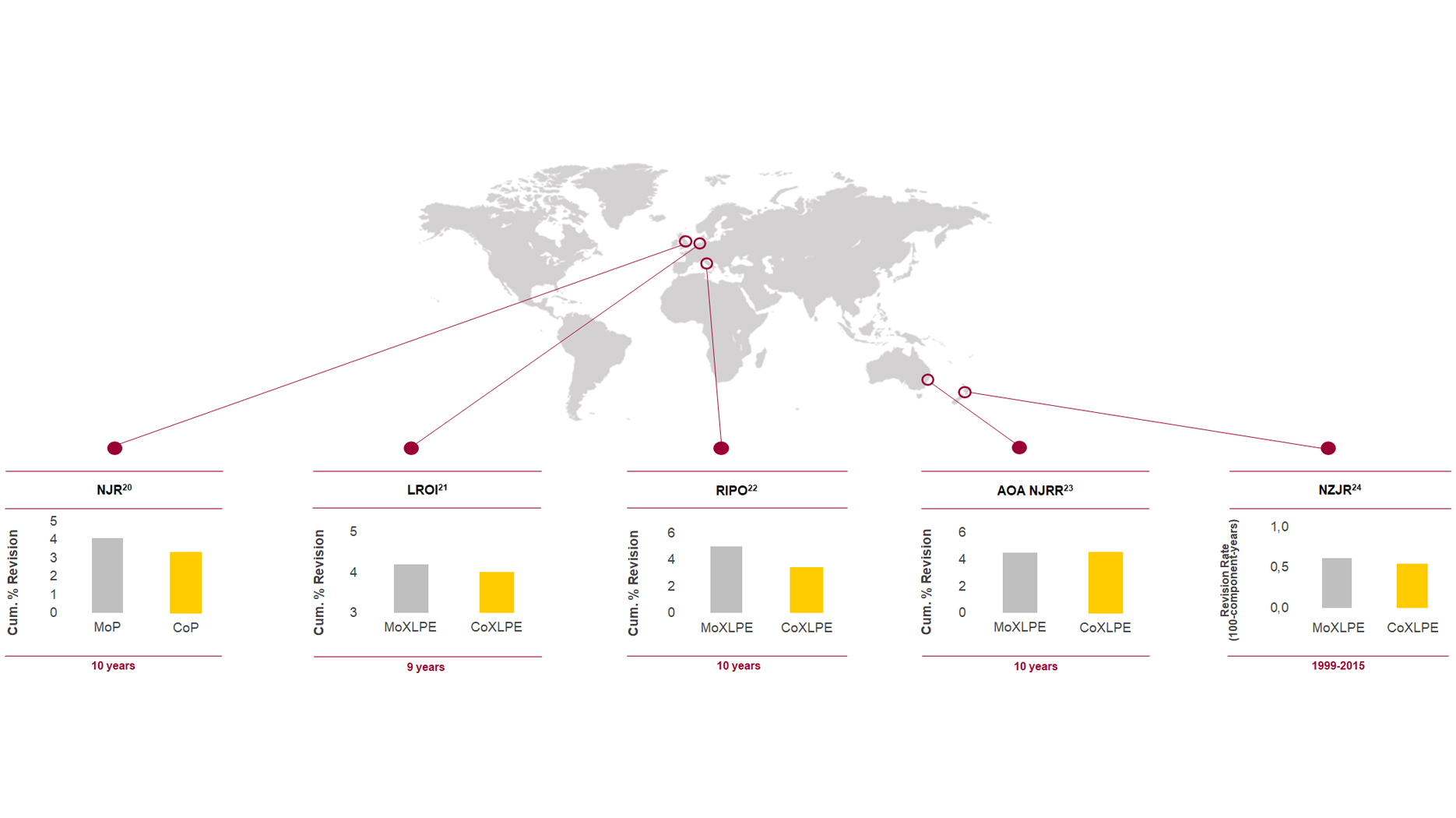

In-vitro and in-vivo studies demonstrate that ceramic is able to “perform its desired function”, “generate an appropriate cellular or tissue response” and “is not likely to elicit adverse local or systemic effects in the host”. Accordingly, ceramic complies with Williams' definition of biocompatibility confirmed at the Chengdu consensus conference in 2018.19 What does it mean for the clinical performance of ceramics? Most arthroplasty registries worldwide confirm that the use of ceramic heads is associated with lower rates of revision compared to metal heads.20-24

1. OECD (2019), Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators, Paris: OECD Publishing; 2019:198. doi:10.1787/4dd50c09-en. Accessed November 5, 2020.

2. Svenska Höftprotesregistret. Årsrapport 2019. 2020:53 (Figure 6.6.1).

3. Registro Regionale di Implantologia Protesica Ortopedica. Dati complessivi interventi di protesi d’anca, di ginocchio e di spalla in Emilia-Romagna 2000-2018. Versione 1 del 02 ottobre 2020. 2020:35-36.

4. American Joint Replacement Registry (AJRR).2020 Annual Report. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). 2020:33 (Figure 2.17).

5. Endoprothesenregister Deutschland (EPRD). Jahresbericht 2020. 2020:22 (Tabelle 14). doi:10.36186/reporteprd022020.

6. Online LROI annual report 2012. Dutch Arthroplasty Register (LROI) website. www.lroi-report.nl/hip/total-hip-arthroplasty/materials/. Accessed November 6, 2020.

7. National Joint Registry for England, Wales. Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man, 17th Annual Report 2020. Surgical data to 31 December 2019. 2020:44-45 (Table 3.H2).

8. The New Zealand Joint Registry. Twenty year report (January 1999 - December 2018). 2019:16.

9. Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR). Hip, Knee & Shoulder Arthroplasty: 2020 Annual Report. Adelaide:AOA. 2020:151.

10. National Joint Registry for England, Wales. Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man, 17th Annual Report 2020. Surgical data to 31 December 2019. ISSN 2054-183X (Online) 2020:189 (Table 3.K16a).

11. National Joint Registry for England, Wales. Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man, 17th Annual Report 2020. Surgical data to 31 December 2019. ISSN 2054-183X (Online) 2020:114 (Tables 3.H17a).

12. Gonzalez A, Garavaglia G, Peter R, Hoffmeyer P, Hannouche D, Lübbeke A. Influence of smoking status on risk of revision after primary total hip arthroplasty is bearing-dependent. In: Proceedings from 8th International Congress of Arthroplasty Registries; June 1-3, 2019; Leiden, Netherlands. 2019; Abstract No. 39.

13. Kocagoz SB, Underwood RJ, MacDonald DW, Gilbert JL, Kurtz SM. Ceramic heads decrease metal release caused by head-taper fretting and corrosion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(4):985-994. doi:10.1007/s11999-015-4683-1.

14. Asif I M. Characterisation and Biological Impact of Wear Particles from Composite Ceramic Hip Replacements. [PhD thesis]. Leeds, UK: University of Leeds; 2018. etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/20563. Accessed March 6, 2020.

15. Wight CM, Lanting B, Schemitsch EH. Evidence based recommendations for reducing head-neck taper connection fretting corrosion in hip replacement prostheses. Hip Int. 2017;27(6):523-531. doi:10.5301/hipint.5000545.

16. Lenguerrand E, Whitehouse MR, Beswick AD, et al. Risk factors associated with revision for prosthetic joint infection after hip replacement: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(9):1004-1014. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30755-2.

17. Al-Hajjar M, Fisher J, Hardaker C, Kurring G, Thompson J, Williams S. Wear of Large Diameter Ceramic-on-Ceramic Bearings in Total Hip Replacements under Edge Loading Conditions. Paper presented at: 60th Anniversary Meeting of Orthopaedic Research Society (ORS); March 15 March 18, 2014 2014 to Mar; New Orleans, LA, USA Abstract 1818.

18. Hernigou P, Homma Y, Pidet O, Guissou I, Hernigou J. Ceramic-on-ceramic bearing decreases the cumulative long-term risk of dislocation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(12):3875-3882. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-2857-2.

19. Ghasemi-Mobarakeh L, Kolahreez D, Ramakrishna S, Williams D. Key terminology in biomaterials and biocompatibility. Curr Opin Biomed Eng. 2019;10:45-50. doi:10.1016/j.cobme.2019.02.004.

20. National Joint Registry for England, Wales. Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man, 15th Annual Report 2018. Surgical data to 31 December 2017.ISSN 2054-1821 (Print) 2018:50 (table 3.7).

21. Peters RM, Van Steenbergen LN, Stevens M, Rijk PC, Bulstra SK, Zijlstra WP. The effect of bearing type on the outcome of total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthopaedica. 2018,89(2):163-169. doi:10.1080/17453674.2017.1405669.

22. Report of R.I.P.O. Regional Register of Orthopaedic Prosthetic Implantology Overall Data Hip, Knee and Shoulder Arthroplasty in Emilia-Romagna Region (Italy) 2000-2016. 2018:57.

23. Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR). Hip, Knee & Shoulder Arthroplasty: 2018 Annual Report. Data period 1 September 1999 – 31 December 2017. Adelaide: AOA, 2018:157 (table HT30).

24. Sharplin P, Wyatt MC, Rothwell A, Frampton C, Hooper G. Which is the best bearing surface for primary total hip replacement? A New Zealand Joint Registry study. Hip Int. 2017;28(4):352-362. doi:10.5301/hipint.5000585.

We support you