The disparity between total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA) patient-perceived outcomes is concerning, with TKA patients being satisfied (80-90%) at a much lower rate than their THA counterparts (94-97%). In many cases the TKA patients have vague subjective complaints about residual pain and swelling, an achy joint, or an inability to kneel or squat. Other more objective complaints may include a skin rash or constant or recurrent effusions in a joint. After infection has been ruled out along with implant suboptimal alignment, instability and other causes of residual pain, a metal hypersensitivity reaction must be considered.

While TKA largely has seen decades of successful outcomes, as clinicians we should focus on improving the number of patients who are satisfied after their TKA. Over the last two to three decades a focus on patient perceived outcomes has spotlighted that nearly 1 out of 5 patients may not be satisfied with their TKA result. About 15 years ago, dermatologists suggested that orthopaedic surgeons begin skin-patch testing (SPT) of patients before insertion of metal implants. It was then suggested that the patients with poorer outcomes could be suffering from a metal hypersensitivity reaction. Over the last two decades dermatologists have noted that nickel allergy in patients continues to climb when skin-patch testing results are compared over time. In North America, such sensitivity has been reported in over 18% of individuals. But several authors in this publication point out the inherent issues with relying on SPT when applied to the presence of an implant in deep tissue. (In 2011, along with Drs. Josh Jacobs and Stuart Goodman, we published a rebuttal to the first dermatology suggestion of SPT for all orthopaedic patients in AAOS Now (ref)). Today, there is still not enough data to suggest that this recommendation should be followed. In this issue of CeraNews, experts point out that SPT reactions rely on langerhan cells which are dendritic-derived cells, whereas deep-tissue reactions are driven by lymphocytes, monocytes, local cytokines, and antibodies. There also have been multiple reports where a SPT has converted after an implant was placed in a patient and cases where a patient with a nickel-positive SPT experienced a good clinical outcome after undergoing a primary TKA that had trace nickel in its alloy.

Many orthopaedic surgeons still consider metal hypersensitivity as a cause for pain and dissatisfaction after a TKA as a diagnosis of exclusion. When a metal hypersensitivity reaction is suspected, surgeons should rule out all other common causes (i.e. infection, arthrofibrosis, suboptimal implant alignment) before going down the metal hypersensitivity pathway. Complaints of recurrent or constant effusion, continued pain, and never having a period of satisfaction also are common symptoms of a septic low-level infection, which is why it is imperative that infection first be ruled out. In the U.S., we are limited in the tests that we can order. While a lymphocyte transformation test (LTT) is available in most laboratories, not all insurance companies will cover its cost and not all labs have consistent protocols, which makes it difficult to rely on some results. Dermatologists can perform a SPT, but these typically cost well over $1,000. Melisa tests are not readily available and genetic testing has not become available or approved in the USA. (As you will read in this issue, the test has had promising results and is being used in other countries.)

Genetic testing is the newest diagnostic test on the scene, based mostly on the ALVAL determinants from our Metal on Metal (MoM) hip arthroplasty bearing surface experiences. ALVAL is now looking like a scenario that occurs more often in TKA revisions than previously thought, with up to 30% of TKA revision surgeries showing evidence of ALVAL. Taking into account the number of revisions in the first five years after primary TKA and then the fact that 30% of patients may show signs of ALVAL, this may represent a more true numerator of hypersensitivity reactions after TKA surgery. While a number of publications have shown improvements of metal hypersensitivity-diagnosed patients after undergoing revision TKA surgery with an alternative implant material (ceramic coatings, ceramicized metals, BIOLOX delta or Alumina implants), there also have been reports of patients who have not seen improvements after exchanging their implants for ones made of a nickel/cobalt chrome-free biomaterial.

Dr. Summer, from the Munich Implant Allergy group, reports in this edition that they advocate a multifaceted approach to diagnosis of implant hypersensitivity. Using SPT along with LTT results as well as IL1alpha and beta stimulation testing and genetic testing is beneficial. Their genetic testing focuses on identifying single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) of IL1RN. They think that by identifying these variants they can help predict which implants may be best on an individual basis.

Dr. Caicedo, in this edition, discusses the fact that genetic testing is in its early stages. He says utilizing human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotypes in patients who had ALVAL reactions might help some patients, but that specific clinical outcomes based on these results may be challenging.

We performed a single nucleotide polymorphism study on 44 patients with symptomatic pain and high cobalt and chrome levels after MoM THA and could not find a correlation with any SNPs that were identified. (Mihalko et al ISTA 2015) There was a weak association with an SNP for IL-15 in some patients with high cobalt and chrome circulating blood levels, but it was found to not be consistent.

For decades now, the literature has focused on nickel. Dr. Langton, in this edition, discusses how nickel allergy in orthopaedics has been ill defined as a cause of arthroplasty failure. While there are trace amounts of nickel in the grain boundaries of cobalt-chrome alloys, we know that cobalt-chrome alloys have been used for decades in a very successful manner. Dr. Langton’s group also reports on how many ALVAL patients from MoM hip-bearing cases were found to have positive LTT results for nickel.

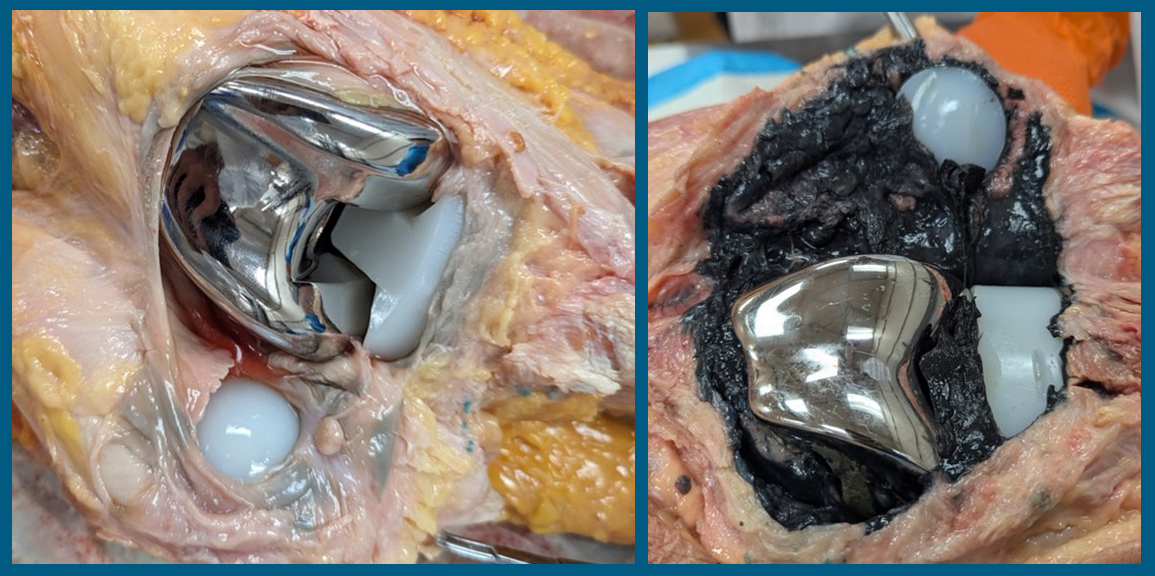

We know that these cobalt-chrome alloys have been labeled as the cause of hypersensitivity reactions, based on our experiences with MoM and taper-corrosion issues in total hip arthroplasty with ALVAL reactions. In the European Union, cobalt-containing implants are now labeled as carcinogenic. This has alerted the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to focus on the possibility of cobalt-chrome alloys in TKA being an issue in a subset of patients. A research focus group (ARCTIC-Arthroplasty Retrieval and Cellular Tissue Investigation Consortium) was established after supporting a multi-center retrieval study by the FDA. Some preliminary results from revision and necropsy-retrieved synovial tissues around TKA implants have showed that no nickel has been detectable, but larger amounts of chromium compared with cobalt are consistently being found in the synovium adjacent to CoCr TKA implants. In comparing bilateral synovial tissue in necropsy specimens where one side has a TKA and the other a native knee, there are significantly higher cobalt and chrome levels on the TKA side. Another recent report has linked the amount of Co and Cr found in the synovium via inductively coupled mass spectrometry (ICPMS) analysis to be correlated to time of implantation. (Kurtz et al 2024) These preliminary findings suggest that the presence of the cobalt chrome implant has a local and systemic effect on the body with time; this might be one of the avenues of hypersensitization in a subset of TKA patients. We have also found necropsy specimens where a significant amount of metal laden synovium was visually present, making no question that a patient could get sensitized to the metal alloy byproducts (Figure 1).

Figure 1A and B:Two examples of necropsy retrievals. A (left) shows mild synovial gray metal staining where B (right) shows severe metalosis of the entire surrounding synovial layer. Neither example showed any evidence of metal contact between the bearing or non-bearing surfaces, but the one on the right did have a periprosthetic femur fracture fixed with a side plate. Again, there was no evidence of implant metal contact.

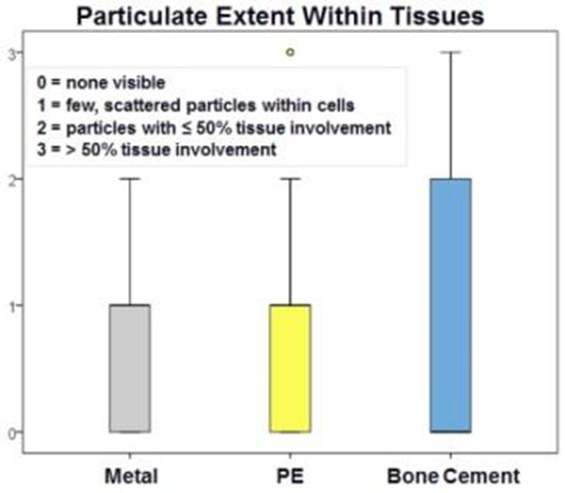

Other biomaterial by-products, however, also have been found in the synovial tissue at much higher rates in our repository study. Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) has been found in histology-prepared samples from this study group far more often than other metals (Figure 2).(ORS podium presentation 2025)

A recent 2025 report on 50 nickel-allergy patients undergoing TKA found no correlation with poor outcomes and severity of nickel allergy (Chimento et al 2025). However, a recent meta-analysis that included eight articles and over 33,000 TKA patients found that metal-allergy patients had poorer reported outcomes (Soler et al 2024). Siljander et al just reported on 287 patients who had a self-reported nickel allergy and compared them with a large cohort of patients without a self-reported allergy and found no difference in revision rates or with outcomes (Siljander et al 2024). Clearly, the literature shows mixed results when it comes to nickel allergy and TKA outcomes.

Revision is not always the answer

While newer diagnostic tools, such as genetic testing, have been developed from what we learned during the MoM ALVAL reactions, a perfect correlation to TKA may not be evident. Also, the ALVAL reactions and circulating metal levels may not show a correlation with genetic testing. The Mayo Clinic in 2016 reported on 161 primary TKAs (127 patients, 56 SPT positive) after SPT compared them with a matched control group of 161 TKAs and found no difference in failures at 5 years or in outcomes. Clearly this study determined a positive SPT may not be consequential and revision may not always make a difference. I personally have seen patients in my practice with a painful and chronic effusion after a primary TKA with a diagnosis of exclusion and a positive SPT and LTT for nickel that had no improvement with revision surgery. Therefore, I inform patients that revision surgery cannot always be relied on for improved results.

The problem remains and more data is necessary

While SPT, LTT, and lymphocyte proliferation testing have all been used for diagnosing metal allergy in TKA patients, there has not been a reported good correlation between these tests in the literature. (Dennis 2022, Malihias 2023) Careful assessment of genetic results should be taken into consideration. As has been explained above, a hypersensitivity reaction requires a pre-sensitized host. Previous exposure to the metal antigen triggers an initial immune cascade, and when re-exposed an exaggerated immunological reaction can occur. Sometimes it takes repeated exposure to an antigen before a true reaction occurs. Environmental and geographical location also have been shown to affect the patients’ sensitization to metals. Many reports in the literature have shown good outcomes after TKA in patients with self-reported or positive SPT, so there may not be a perfect correlation with a significant false positive rate of results. According to SPT results, metal sensitivity in the general population is approximately 18% nickel, 7% cobalt (cobalt chloride), 3% chromium (dichromate), and cross-reactivity between nickel and cobalt is thought to be common. That being said, I do not believe that surgeons feel that we are seeing 20% or higher rates of orthopaedic-implant patients with a metal hypersensitivity diagnosis. Clearly, the issue is more complicated and deep-tissue reactions may not be as prevalent. This brings up another issue with SPT because as mentioned above the metal byproducts utilized in SPT are not the same as those produced in the deep joint tissues from cobalt chrome or other orthopaedic implant alloys.

Continued research

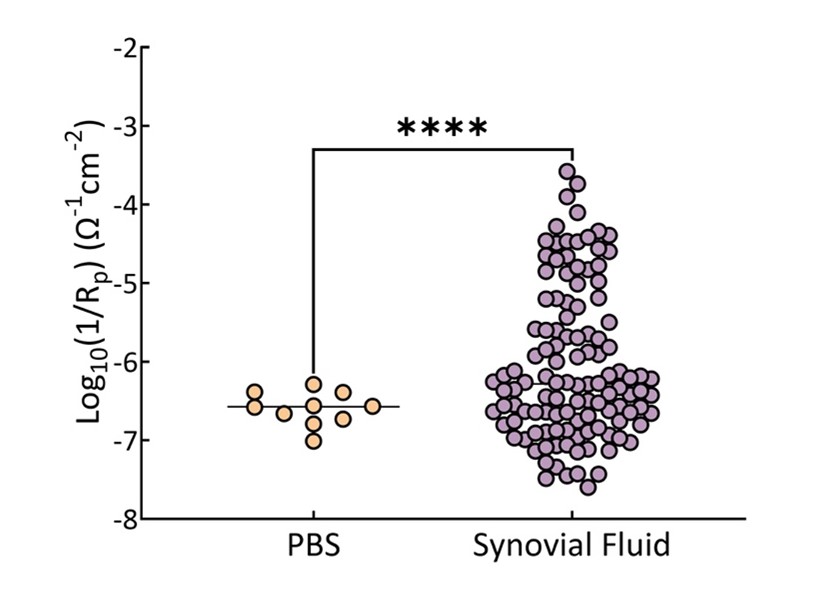

Local physiological environment around the implant may also have an impact on metal release around a femoral component after a TKA. We have hypothesized in my lab that inflammatory cell-induced corrosion (ICIC) may contribute to metal release of Co and Cr in a subset of individuals. While the pits on retrievals from revision THA/TKA have been reported at a high incidence (up to 60% in some retrieval archives), we have found that in our necropsy-retrieval archive that the evidence was much lower (17%). This was most likely due to the fact that necropsy-retrieved implants are much less likely to be exposed to electrocautery effects (which has been proven to cause these pits found on implants). During revision surgery, most surgeons utilize electrocautery around the implant to aid in extraction. We have also found that in a small percentage of OA synovial fluid samples obtained during TKA surgery there was a significantly higher corrosion rate against CoCr (an order of magnitude greater corrosion rate in 5% of patients).

Figure 3: Log scale range of corrosion rates for phosphate buffered saline compared with osteoarthritis synovial fluid obtained at time of primary TKA. More than an order of magnitude variation against CoCr was seen for OA synovial fluid. This variation could accelerate corrosion by-products being released after implantation of a CoCr femoral component adding to sensitization of the host.

So local physiology combined with environmental exposure could be sensitizing patients after their TKA, which might cause local inflammatory response and a poor patient-reported outcome. We continue to follow these patients with high synovial fluid corrosion rates longitudinally to determine if there is a correlation with Knee Injury Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Joint Replacement (KOOSJR) scores. To date, the parameters found to correlate with outcome scores are higher volume of synovial fluid at the time of surgery and pH.

There is clearly a void in that data we need to analyze to determine who truly has and who may develop a metal hypersensitivity reaction.

Acknowledgment

I want to thank the authors for their expertise and reporting in this edition of CeraNews and their help in bringing a focus on this potential issue in TKA patients causing poor outcomes. I also want to acknowledge the ARCTIC study group for the insights reported above concerning metal release around TKA implants. I thank my collaborators in the Arthroplasty Retrieval and Cellular Tissue Investigation Consortium (ARCTIC) study group:

Steven Kurtz PhD, (Drexel University);

Michael Kurtz PhD (Drexel University);

Nicholas Piuzzi MD (Cleveland Clinic);

Jeremy Gilbert PhD (Clemson University);

Robin Pourzal PhD, (Rush University);

Deborah Hall PhD (Rush University).

1. Breuer R, Fiala R, Hartenbach F, Pollok F, Huber T, Strasser-Kirchweger B, Rath B, Trieb K. Long term follow-up of a completely metal free total knee endoprosthesis in comparison to an identical metal counterpart. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):20958. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-71256-y

2. Chimento G, Daher J, Desai B, Velasco-Gonzalez C. Nickel allergy does not correlate with function after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2025;33(2):646-653. doi: 10.1002/ksa.12448

3. Xie F, Sheng S, Ram V, Pandit H. Hypoallergenic knee implant usage and clinical outcomes: are they safe and effective? Arthroplast Today. 2024;28:101399. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2024.101399

4. Soler F, Murcia A, Benlloch M, Mariscal G. The impact of allergies on patient-reported outcomes after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2024;144(8):3755-3765. doi: 10.1007/s00402-024-05433-z

5. Siljander BR, Chandi SK, Cororaton AD, Debbi EM, McLawhorn AS, Sculco PK, Chalmers BP. A comparison of clinical outcomes after total knee arthroplasty in patients who have and do not have self-reported nickel allergy: matched and unmatched cohort comparisons. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39(10):2490-2495. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2024.05.029

6. Tidd JL, Gudapati LS, Simmons HL, Klika AK, Pasqualini I; Cleveland Clinic Arthroplasty Group; Piuzzi NS. Do patients with hypoallergenic total knee arthroplasty implants for metal allergy do worse? an analysis of health care utilizations and patient-reported outcome measures. J Arthroplasty. 2024;39(1):103-110. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2023.07.005

7. Siljander BR, Chandi SK, Debbi EM, McLawhorn AS, Sculco PK, Chalmers BP. A comparison of clinical outcomes after total knee arthroplasty in patients with preoperative nickel allergy receiving cobalt chromium or nickel-free implant. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38(7 Suppl 2):S194-S198. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2023.04.048

8. Bracey DN, Hegde V, Johnson R, Kleeman-Forsthuber L, Jennings J, Dennis D. Poor correlation among metal hypersensitivity testing modalities and inferior patient-reported outcomes after primary and revision total knee arthroplasties. Arthroplast Today. 2022;18:138-142. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2022.09.016

9. Peacock CJH, Fu H, Asopa V, Clement ND, Kader D, Sochart DH. The effect of nickel hypersensitivity on the outcome of total kneearthroplasty and the value of skin patch testing: a systematic review. Arthroplasty. 2022 Sep 2;4(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s42836-022-00144-5.PMID: 36050799

10. Brozovich A, Clyburn T, Park K, Harper KD, Sullivan T, Incavo S, Taraballi F. Evaluation of local tissue peri-implant reaction in total knee arthroplasty failure cases. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2022;14:1759720X221092263. doi: 10.1177/1759720X221092263

11. Matar HE, Porter PJ, Porter ML. Metal allergy in primary and revision total knee arthroplasty: a scoping review and evidence-based practical approach.Bone Jt Open. 2021;2(10):785-795. doi: 10.1302/2633-1462.210.BJO-2021-0098.R1

12. Pahlavan S, Hegde V, Bracey DN, Jennings JM, Dennis DA. Bone cement hypersensitivity in patients with a painful total knee arthroplasty: a case series of revision using custom cementless implants. Arthroplast Today. 2021;11:20-24. doi: 10.1016/j.artd.2021.06.001

13. Peña P, Ortega MA, Buján J, De la Torre B. Influence of psychological distress in patients with hypoallergenic total knee arthroplasty. treatment algorithm for patients with metal allergy and knee osteoarthritis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11):5997. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18115997

14. Breuer R, Fiala R, Trieb K, Rath B. Prospective mid-term results of a completely metal-free ceramic total knee endoprosthesis: a concise follow-up of a previous report. J Arthroplasty. 2021;36(9):3161-3167. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2021.05.007

15. Malahias MA, Bauer TW, Manolopoulos PP, Sculco PK, Westrich GH. Allergy testing has no correlation with intraoperative histopathology from revision total knee arthroplasty for implant-related metal allergy. J Knee Surg. 2023;36(1):6-17. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1729618

16. D'Ambrosi R, Nuara A, Mariani I, Di Feo F, Ursino N, Hirschmann M. Titanium niobium nitride mobile-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty results in good to excellent clinical and radiographic outcomes in metal allergy patients with medial knee osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2021;36(1):140-147.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.07.028

17. Richards LJ, Streifel A, Rodrigues JM. Utility of patch testing and lymphocyte transformation testing in the evaluation of metal allergy in patients with orthopedic implants. Cureus. 2019;11(9):e5761. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5761

18. Sasseville D, Alfalah K, Savin E. Patch test results and outcome in patients with complications from total knee arthroplasty: a consecutive case series. J Knee Surg. 2021;34(3):233-241. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1694984

19. Zondervan RL, Vaux JJ, Blackmer MJ, Brazier BG, Taunt CJ Jr. Improved outcomes in patients with positive metal sensitivity following revision total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14(1):182. doi: 10.1186/s13018-019-1228-4

20. Yang S, Dipane M, Lu CH, Schmalzried TP, McPherson EJ. Lymphocyte transformation testing (LTT) in cases of pain following total knee arthroplasty: little relationship to histopathologic findings and revision outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101(3):257-264. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.18.00134.PMID: 30730485

21. Thomas P, Hisgen P, Kiefer H, Schmerwitz U, Ottersbach A, Albrecht D, Summer B, Schinkel C. Blood cytokine pattern and clinical outcome in knee arthroplasty patients: comparative analysis 5 years after standard versus "hypoallergenic" surface coated prosthesis implantation. Acta Orthop. 2018;89(6):646-651. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2018.1518802

22. Jauregui JJ, Desai SJ, Hodges V, Hariharan A, Newman JM, Adib F, Maheshwari AV. Outcomes of revision joint arthroplasty due to metal allergy and hypersensitivity: a systematic review. Surg Technol Int. 2018; 33:332-336. PMID: 29985516

23. Akil S, Newman JM, Shah NV, Ahmed N, Deshmukh AJ, Maheshwari AV. Metal hypersensitivity in total hip and knee arthroplasty: current concepts. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2018;9(1):3-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2017.10.003

24. Mitchelson AJ, Wilson CJ, Mihalko WM, Grupp TM, Manning BT, Dennis DA, Goodman SB, Tzeng TH, Vasdev S, Saleh KJ. Biomaterial hypersensitivity: is it real? Supportive evidence and approach considerations for metal allergic patients following total knee arthroplasty. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:137287. doi: 10.1155/2015/137287

25. Lachiewicz PF, Watters TS, Jacobs JJ. Metal hypersensitivity and total knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24(2):106–112. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-14-00290

26. DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Reeder MJ, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group Patch Test Results: 2019-2020. Dermatitis. 2023;34(2) 90-104. doi: 10.1089/derm.2022.29017.jdk

27. Silverberg JI, Patel N, Warshaw EM, et al. Patch testing with nickel cobalt and chromium in patients with suspected allergic contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2024;35(2) 152-159. doi:10.1089/derm.2023.0139.

28. Bravo D, Wagner ER, Larson DR, Davis MP, Pagnano MW, Sierra RJ. No increased risk of knee arthroplasty failure in patients with positive skin patch testing for metal hypersensitivity: a matched cohort study. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(8):1717-21. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.01.024.

29. Mihalko WM, Goodman SB, Amini M, et al. Metal sensitivity testing and associated total joint outcomes. 2013 American Academy of Oorthopaedic Surgeons annual meeting. Scientific exhibit presentation. Chicago, IL.